Images and Sprites

pyglet provides functions for loading and saving images in various formats using native operating system services. If the Pillow library is installed, many additional formats can be supported. pyglet also includes built-in codecs for loading PNG and BMP without external dependencies.

Loaded images can be efficiently provided to OpenGL as a texture, and OpenGL textures and framebuffers can be retrieved as pyglet images to be saved or otherwise manipulated.

If you’ve done any game or graphics programming, you’re probably familiar with

the concept of “sprites”. pyglet also provides an efficient and comprehensive

Sprite class, for displaying images on the screen

with an optional transform (such as scaling and rotation). If you’re planning

to do anything with images that involves movement and placement on screen,

you’ll likely want to use sprites.

Loading an image

Images can be loaded using the pyglet.image.load() function:

kitten = pyglet.image.load('kitten.png')

If you are distributing your application with included images, consider

using the pyglet.resource module (see Application resources).

Without any additional arguments, pyglet.image.load() will

attempt to load the filename specified using any available image decoder.

This will allow you to load PNG, GIF, JPEG, BMP and DDS files,

and possibly other files as well, depending on your operating system

and additional installed modules (see the next section for details).

If the image cannot be loaded, an

ImageDecodeException will be raised.

You can load an image from any file-like object providing a read method by specifying the file keyword parameter:

kitten_stream = open('kitten.png', 'rb')

kitten = pyglet.image.load('kitten.png', file=kitten_stream)

In this case the filename kitten.png is optional, but gives a hint to

the decoder as to the file type (it is otherwise unused when a file object

is provided).

Displaying images

Image drawing is usually done in the window’s

on_draw() event handler.

It is possible to draw individual images directly, but usually you will

want to create a “sprite” for each appearance of the image on-screen.

Sprites

A Sprite is a full featured class for displaying instances of Images or Animations in the window. Image and Animation instances are mainly concerned with the image data (size, pixels, etc.), wheras Sprites also include additional properties. These include x/y location, scale, rotation, opacity, color tint, visibility, and both horizontal and vertical scaling. Multiple sprites can share the same image; for example, hundreds of bullet sprites might share the same bullet image.

A Sprite is constructed given an image or animation, and can be directly

drawn with the draw() method:

sprite = pyglet.sprite.Sprite(img=image)

@window.event

def on_draw():

window.clear()

sprite.draw()

If created with an animation, sprites automatically handle displaying the most up-to-date frame of the animation. The following example uses a scheduled function to gradually move the Sprite across the screen:

def update(dt):

# Move 10 pixels per second

sprite.x += dt * 10

# Call update 60 times a second

pyglet.clock.schedule_interval(update, 1/60.)

If you need to draw many sprites, using a Batch

to draw them all at once is strongly recommended. This is far more efficient

than calling draw() on each of them in a loop:

batch = pyglet.graphics.Batch()

sprites = [pyglet.sprite.Sprite(image, batch=batch),

pyglet.sprite.Sprite(image, batch=batch),

# ... ]

@window.event

def on_draw():

window.clear()

batch.draw()

When sprites are collected into a batch, no guarantee is made about the order

in which they will be drawn. If you need to ensure some sprites are drawn

before others (for example, landscape tiles might be drawn before character

sprites, which might be drawn before some particle effect sprites), use two

or more OrderedGroup objects to specify the

draw order:

batch = pyglet.graphics.Batch()

background = pyglet.graphics.OrderedGroup(0)

foreground = pyglet.graphics.OrderedGroup(1)

sprites = [pyglet.sprite.Sprite(image, batch=batch, group=background),

pyglet.sprite.Sprite(image, batch=batch, group=background),

pyglet.sprite.Sprite(image, batch=batch, group=foreground),

pyglet.sprite.Sprite(image, batch=batch, group=foreground),

# ...]

@window.event

def on_draw():

window.clear()

batch.draw()

For best performance, you should use as few batches and groups as required. (See the Shaders and Rendering section for more details on batch and group rendering). This will reduce the number of internal and OpenGL operations for drawing each frame.

In addition, try to combine your images into as few textures as possible;

for example, by loading images with pyglet.resource.image()

(see Application resources) or with Texture bins and atlases).

A common pitfall is to use the pyglet.image.load() method to load

a large number of images. This will cause a seperate texture to be created

for each image loaded, resulting in a lot of OpenGL texture binding overhead

for each frame.

Simple image blitting

Drawing images directly is less efficient, but may be adequate for

simple cases. Images can be drawn into a window with the

blit() method:

@window.event

def on_draw():

window.clear()

image.blit(x, y)

The x and y coordinates locate where to draw the anchor point of the

image. For example, to center the image at (x, y):

kitten.anchor_x = kitten.width // 2

kitten.anchor_y = kitten.height // 2

kitten.blit(x, y)

You can also specify an optional z component to the

blit() method.

This has no effect unless you have changed the default projection

or enabled depth testing. In the following example, the second

image is drawn behind the first, even though it is drawn after it:

from pyglet.gl import *

glEnable(GL_DEPTH_TEST)

kitten.blit(x, y, 0)

kitten.blit(x, y, -0.5)

The default pyglet projection has a depth range of (-1, 1) – images drawn with a z value outside this range will not be visible, regardless of whether depth testing is enabled or not.

Images with an alpha channel can be blended with the existing framebuffer. To do this you need to supply OpenGL with a blend equation. The following code fragment implements the most common form of alpha blending, however other techniques are also possible:

from pyglet.gl import *

glEnable(GL_BLEND)

glBlendFunc(GL_SRC_ALPHA, GL_ONE_MINUS_SRC_ALPHA)

You would only need to call the code above once during your program, before you draw any images (this is not necessary when using only sprites).

Supported image decoders

The following table shows which codecs are available in pyglet.

Module

Class

Description

pyglet.image.codecs.dds

DDSImageDecoderReads Microsoft DirectDraw Surface files containing compressed textures

pyglet.image.codecs.wic

WICDecoderUses Windows Imaging Component services to decode images.

pyglet.image.codecs.gdiplus

GDIPlusDecoderUses Windows GDI+ services to decode images.

pyglet.image.codecs.gdkpixbuf2

GdkPixbuf2ImageDecoderUses the GTK-2.0 GDK functions to decode images.

pyglet.image.codecs.pil

PILImageDecoderWrapper interface around PIL Image class.

pyglet.image.codecs.quicktime

QuickTimeImageDecoderUses Mac OS X QuickTime to decode images.

pyglet.image.codecs.png

PNGImageDecoderPNG decoder written in pure Python.

pyglet.image.codecs.bmp

BMPImageDecoderBMP decoder written in pure Python.

Each of these classes registers itself with pyglet.image with

the filename extensions it supports. The load()

function will try each image decoder with a matching file extension first,

before attempting the other decoders. Only if every image decoder fails

to load an image will ImageDecodeException

be raised (the origin of the exception will be the first decoder that

was attempted).

You can override this behaviour and specify a particular decoding instance to use. For example, in the following example the pure Python PNG decoder is always used rather than the operating system’s decoder:

from pyglet.image.codecs.png import PNGImageDecoder

kitten = pyglet.image.load('kitten.png', decoder=PNGImageDecoder())

This use is not recommended unless your application has to work around specific deficiences in an operating system decoder.

Supported image formats

The following table lists the image formats that can be loaded on each operating system. If Pillow is installed, any additional formats it supports can also be read. See the Pillow docs for a list of such formats.

Extension

Description

Windows

Mac OS X

Linux [5]

.bmpWindows Bitmap

X

X

X

.ddsMicrosoft DirectDraw Surface [6]

X

X

X

.exifExif

X

.gifGraphics Interchange Format

X

X

X

.jpg .jpegJPEG/JIFF Image

X

X

X

.jp2 .jpxJPEG 2000

X

.pcxPC Paintbrush Bitmap Graphic

X

.pngPortable Network Graphic

X

X

X

.pnmPBM Portable Any Map Graphic Bitmap

X

.rasSun raster graphic

X

.tgaTruevision Targa Graphic

X

.tif .tiffTagged Image File Format

X

X

X

.xbmX11 bitmap

X

X

.xpmX11 icon

X

X

The only supported save format is PNG, unless PIL is installed, in which case any format it supports can be written.

Working with images

The pyglet.image.load() function returns an

AbstractImage. The actual class of the object depends

on the decoder that was used, but all loaded imageswill have the following

attributes:

- width

The width of the image, in pixels.

- height

The height of the image, in pixels.

- anchor_x

Distance of the anchor point from the left edge of the image, in pixels

- anchor_y

Distance of the anchor point from the bottom edge of the image, in pixels

The anchor point defaults to (0, 0), though some image formats may contain an intrinsic anchor point. The anchor point is used to align the image to a point in space when drawing it.

You may only want to use a portion of the complete image. You can use the

get_region() method to return an image

of a rectangular region of a source image:

image_part = kitten.get_region(x=10, y=10, width=100, height=100)

This returns an image with dimensions 100x100. The region extracted from kitten is aligned such that the bottom-left corner of the rectangle is 10 pixels from the left and 10 pixels from the bottom of the image.

Image regions can be used as if they were complete images. Note that changes to an image region may or may not be reflected on the source image, and changes to the source image may or may not be reflected on any region images. You should not assume either behaviour.

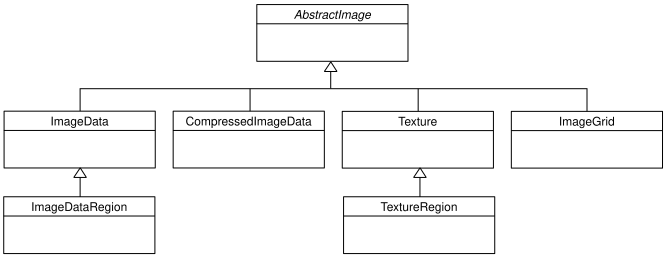

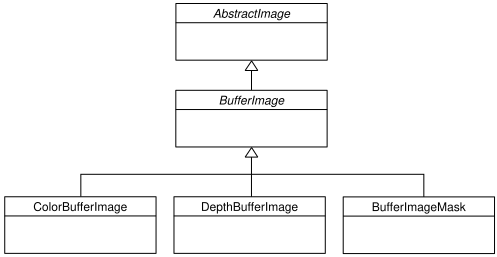

The AbstractImage hierarchy

The following sections deal with the various concrete image classes. All

images subclass AbstractImage, which provides

the basic interface described in previous sections.

The AbstractImage class hierarchy.

An image of any class can be converted into a Texture

or ImageData using the

get_texture() and

get_image_data() methods defined on

AbstractImage. For example, to load an image

and work with it as an OpenGL texture:

kitten = pyglet.image.load('kitten.png').get_texture()

There is no penalty for accessing one of these methods if object is already of the requested class. The following table shows how concrete classes are converted into other classes:

You should try to avoid conversions which use glGetTexImage2D or

glReadPixels, as these can impose a substantial performance penalty by

transferring data in the “wrong” direction of the video bus, especially on

older hardware.

ImageData caches the texture for future use, so there is no

performance penalty for repeatedly blitting an

ImageData.

If the required texture compression extension is not present, the

image is decompressed in memory and then supplied to OpenGL via

glTexImage2D.

It is not currently possible to retrieve ImageData for compressed

texture images. This feature may be implemented in a future release

of pyglet. One workaround is to create a texture from the compressed

image, then read the image data from the texture; i.e.,

compressed_image.get_texture().get_image_data().

BufferImageMask cannot be converted to

Texture.

Accessing or providing pixel data

The ImageData class represents an image as a string

or sequence of pixel data, or as a ctypes pointer. Details such as the pitch

and component layout are also stored in the class. You can access an

ImageData object for any image with

get_image_data():

kitten = pyglet.image.load('kitten.png').get_image_data()

The design of ImageData is to allow applications

to access the detail in the format they prefer, rather than having to

understand the many formats that each operating system and OpenGL make use of.

The pitch and format properties determine how the bytes are arranged. pitch gives the number of bytes between each consecutive row. The data is assumed to run from left-to-right, bottom-to-top, unless pitch is negative, in which case it runs from left-to-right, top-to-bottom. There is no need for rows to be tightly packed; larger pitch values are often used to align each row to machine word boundaries.

The format property gives the number and order of color components. It is a string of one or more of the letters corresponding to the components in the following table:

R

Red

G

Green

B

Blue

A

Alpha

L

Luminance

I

Intensity

For example, a format string of "RGBA" corresponds to four bytes of

colour data, in the order red, green, blue, alpha. Note that machine

endianness has no impact on the interpretation of a format string.

The length of a format string always gives the number of bytes per pixel. So,

the minimum absolute pitch for a given image is len(kitten.format) *

kitten.width.

To retrieve pixel data in a particular format, use the get_data method,

specifying the desired format and pitch. The following example reads tightly

packed rows in RGB format (the alpha component, if any, will be

discarded):

kitten = kitten.get_image_data()

data = kitten.get_data('RGB', kitten.width * 3)

data always returns a string, however pixel data can be set from a ctypes array, stdlib array, list of byte data, string, or ctypes pointer. To set the image data use set_data, again specifying the format and pitch:

kitten.set_data('RGB', kitten.width * 3, data)

You can also create ImageData directly, by providing

each of these attributes to the constructor. This is any easy way to load

textures into OpenGL from other programs or libraries.

Performance concerns

pyglet can use several methods to transform pixel data from one format to another. It will always try to select the most efficient means. For example, when providing texture data to OpenGL, the following possibilities are examined in order:

Can the data be provided directly using a built-in OpenGL pixel format such as

GL_RGBorGL_RGBA?Is there an extension present that handles this pixel format?

Can the data be transformed with a single regular expression?

If none of the above are possible, the image will be split into separate scanlines and a regular expression replacement done on each; then the lines will be joined together again.

The following table shows which image formats can be used directly with steps 1 and 2 above, as long as the image rows are tightly packed (that is, the pitch is equal to the width times the number of components).

Format

Required extensions

"I"

"L"

"LA"

"R"

"G"

"B"

"A"

"RGB"

"RGBA"

"ARGB"

GL_EXT_bgraandGL_APPLE_packed_pixels

"ABGR"

GL_EXT_abgr

"BGR"

GL_EXT_bgra

"BGRA"

GL_EXT_bgra

If the image data is not in one of these formats, a regular expression will be constructed to pull it into one. If the rows are not tightly packed, or if the image is ordered from top-to-bottom, the rows will be split before the regular expression is applied. Each of these may incur a performance penalty – you should avoid such formats for real-time texture updates if possible.

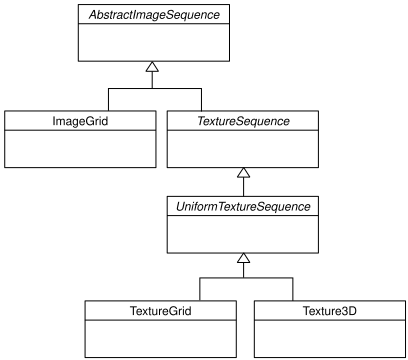

Image sequences and atlases

Sometimes a single image is used to hold several images. For example, a “sprite sheet” is an image that contains each animation frame required for a character sprite animation.

pyglet provides convenience classes for extracting the individual images from such a composite image as if it were a simple Python sequence. Discrete images can also be packed into one or more larger textures with texture bins and atlases.

The AbstractImageSequence class hierarchy.

Image grids

An “image grid” is a single image which is divided into several smaller images by drawing an imaginary grid over it. The following image shows an image used for the explosion animation in the Astraea example.

An image consisting of eight animation frames arranged in a grid.

This image has one row and eight columns. This is all the information you

need to create an ImageGrid with:

explosion = pyglet.image.load('explosion.png')

explosion_seq = pyglet.image.ImageGrid(explosion, 1, 8)

The images within the grid can now be accessed as if they were their own images:

frame_1 = explosion_seq[0]

frame_2 = explosion_seq[1]

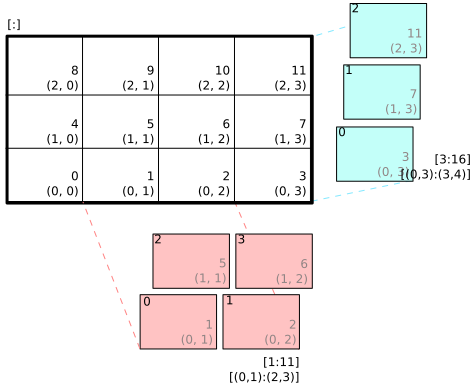

Images with more than one row can be accessed either as a single-dimensional sequence, or as a (row, column) tuple; as shown in the following diagram.

An image grid with several rows and columns, and the slices that can be used to access it.

Image sequences can be sliced like any other sequence in Python. For example, the following obtains the first four frames in the animation:

start_frames = explosion_seq[:4]

For efficient rendering, you should use a

TextureGrid.

This uses a single texture for the grid, and each individual image returned

from a slice will be a TextureRegion:

explosion_tex_seq = image.TextureGrid(explosion_seq)

Because TextureGrid is also a

Texture, you can use it either as individual images

or as the whole grid at once.

3D textures

TextureGrid is extremely efficient for drawing many

sprites from a single texture. One problem you may encounter, however,

is bleeding between adjacent images.

When OpenGL renders a texture to the screen, by default it obtains each pixel

colour by interpolating nearby texels. You can disable this behaviour by

switching to the GL_NEAREST interpolation mode, however you then lose the

benefits of smooth scaling, distortion, rotation and sub-pixel positioning.

You can alleviate the problem by always leaving a 1-pixel clear border around each image frame. This will not solve the problem if you are using mipmapping, however. At this stage you will need a 3D texture.

You can create a 3D texture from any sequence of images, or from an

ImageGrid. The images must all be of the same

dimension, however they need not be powers of two (pyglet takes care of

this by returning TextureRegion

as with a regular Texture).

In the following example, the explosion texture from above is uploaded into a 3D texture:

explosion_3d = pyglet.image.Texture3D.create_for_image_grid(explosion_seq)

You could also have stored each image as a separate file and used

pyglet.image.Texture3D.create_for_images() to create the 3D texture.

Once created, a 3D texture behaves like any other

AbstractImageSequence; slices return

TextureRegion for an image plane within the texture.

Unlike a TextureGrid, though, you cannot blit a

Texture3D in its entirety.

Texture bins and atlases

Image grids are useful when the artist has good tools to construct the larger images of the appropriate format, and the contained images all have the same size. However it is often simpler to keep individual images as separate files on disk, and only combine them into larger textures at runtime for efficiency.

A TextureAtlas is initially an empty texture,

but images of any size can be added to it at any time. The atlas takes care

of tracking the “free” areas within the texture, and of placing images at

appropriate locations within the texture to avoid overlap.

It’s possible for a TextureAtlas to run out

of space for new images, so applications will need to either know the correct

size of the texture to allocate initally, or maintain multiple atlases as

each one fills up.

The TextureBin class provides a simple means

to manage multiple atlases. The following example loads a list of images,

then inserts those images into a texture bin. The resulting list is a list of

TextureRegion images that map

into the larger shared texture atlases:

images = [

pyglet.image.load('img1.png'),

pyglet.image.load('img2.png'),

# ...

]

bin = pyglet.image.atlas.TextureBin()

images = [bin.add(image) for image in images]

The pyglet.resource module (see Application resources) uses

texture bins internally to efficiently pack images automatically.

Animations

While image sequences and atlases provide storage for related images, they alone are not enough to describe a complete animation.

The Animation class manages a list of

AnimationFrame objects, each of

which references an image and a duration (in seconds). The storage of

the images is up to the application developer: they can each be discrete, or

packed into a texture atlas, or any other technique.

An animation can be loaded directly from a GIF 89a image file with

load_animation() (supported on Linux, Mac OS X

and Windows) or constructed manually from a list of images or an image

sequence using the class methods (in which case the timing information

will also need to be provided).

The add_to_texture_bin() method provides

a convenient way to pack the image frames into a texture bin for efficient

access.

Individual frames can be accessed by the application for use with any kind of

rendering, or the entire animation can be used directly with a

Sprite (see next section).

The following example loads a GIF animation and packs the images in that animation into a texture bin. A sprite is used to display the animation in the window:

window = pyglet.window.Window()

animation = pyglet.image.load_animation('animation.gif')

bin = pyglet.image.atlas.TextureBin()

animation.add_to_texture_bin(bin)

sprite = pyglet.sprite.Sprite(img=animation)

@window.event

def on_draw():

window.clear()

sprite.draw()

pyglet.app.run()

When animations are loaded with pyglet.resource (see

Application resources) the frames are automatically packed into a texture bin.

This example program is located in examples/programming_guide/animation.py, along with a sample GIF animation file.

Framebuffers

To simplify working with framebuffers, pyglet provides the

FrameBuffer and RenderBuffer

classes. These work as you would expect, and allow a simple way to add texture

attachments. Attachment and target types can be specified as

from pyglet.gl import *

# Prepare the buffers. One texture (for easy access), and one Renderbuffer:

color_buffer = pyglet.image.Texture.create(width, height, min_filter=GL_NEAREST, mag_filter=GL_NEAREST)

depth_buffer = pyglet.image.Renderbuffer(width, height, GL_DEPTH_COMPONENT)

# Create a Framebuffer, and attach:

framebuffer = pyglet.image.Framebuffer()

framebuffer.attach_texture(color_buffer, attachment=GL_COLOR_ATTACHMENT0)

framebuffer.attach_renderbuffer(depth_buffer, attachment=GL_DEPTH_ATTACHMENT)

# When drawing:

framebuffer.bind()

pyglet also provides a simple abstraction over the “default” framebuffer,

as components of the AbstractImage hierarchy.

The BufferImage hierarchy.

One or more colour buffers, represented by

ColorBufferImageAn optional depth buffer, represented by

DepthBufferImageAn optional stencil buffer, with each bit represented by

BufferImageMask

You cannot create the buffer images directly; instead you must obtain

instances via the BufferManager.

Use get_buffer_manager() to get this singleton:

buffers = image.get_buffer_manager()

Only the back-left color buffer can be obtained (i.e., the front buffer is inaccessible, and stereo contexts are not supported by the buffer manager):

color_buffer = buffers.get_color_buffer()

This buffer can be treated like any other image. For example, you could copy it to a texture, obtain its pixel data, save it to a file, and so on. This can be useful if you want to save a “screen shot” of the running application:

image_data = color_buffer.get_image_data()

image_data.save("screenshot.png")

The depth buffer can be obtained similarly:

depth_buffer = buffers.get_depth_buffer()

The auxiliary buffers and stencil bits are obtained by requesting one, which will then be marked as “in-use”. This permits multiple libraries and your application to work together without clashes in stencil bits or auxiliary buffer names. For example, to obtain a free stencil bit:

mask = buffers.get_buffer_mask()

The buffer manager maintains a weak reference to the buffer mask, so that when you release all references to it, it will be returned to the pool of available masks.

Similarly, a free auxiliary buffer is obtained:

aux_buffer = buffers.get_aux_buffer()

When using the stencil or auxiliary buffers, make sure you explicitly request these when creating the window. See OpenGL configuration options for details.

OpenGL imaging

This section assumes you are familiar with texture mapping in OpenGL (for example, chapter 9 of the OpenGL Programming Guide).

To create a texture from any AbstractImage,

call get_texture():

kitten = image.load('kitten.jpg')

texture = kitten.get_texture()

Textures are automatically created and used by

ImageData when blitted. Itis useful to use

textures directly when aiming for high performance or 3D applications.

The Texture class represents any texture object.

The target attribute gives the

texture target (for example, GL_TEXTURE_2D) and

id the texturename.

For example, to bind a texture:

glBindTexture(texture.target, texture.id)

Texture dimensions

Implementations of OpenGL prior to 2.0 require textures to have dimensions

that are powers of two (i.e., 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, …). Because of this

restriction, pyglet will always create textures of these dimensions (there are

several non-conformant post-2.0 implementations). This could have unexpected

results for a user blitting a texture loaded from a file of non-standard

dimensions. To remedy this, pyglet returns a

TextureRegion of the larger

texture corresponding to just the part of the texture covered by the original

image.

A TextureRegion has an owner attribute that

references the larger texture. The following session demonstrates this:

>>> rgba = image.load('tests/image/rgba.png')

>>> rgba

<ImageData 235x257> # The image is 235x257

>>> rgba.get_texture()

<TextureRegion 235x257> # The returned texture is a region

>>> rgba.get_texture().owner

<Texture 256x512> # The owning texture has power-2 dimensions

>>>

A TextureRegion defines a

tex_coords attribute that gives

the texture coordinates to use for a quad mapping the whole image.

tex_coords is a 4-tuple of 3-tuple

of floats; i.e., each texture coordinate is given in 3 dimensions.

The following code can be used to render a quad for a texture region:

texture = kitten.get_texture()

t = texture.tex_coords

w, h = texture.width, texture.height

array = (GLfloat * 32)(

t[0][0], t[0][1], t[0][2], 1.,

x, y, z, 1.,

t[1][0], t[1][1], t[1][2], 1.,

x + w, y, z, 1.,

t[2][0], t[2][1], t[2][2], 1.,

x + w, y + h, z, 1.,

t[3][0], t[3][1], t[3][2], 1.,

x, y + h, z, 1.)

glPushClientAttrib(GL_CLIENT_VERTEX_ARRAY_BIT)

glInterleavedArrays(GL_T4F_V4F, 0, array)

glDrawArrays(GL_QUADS, 0, 4)

glPopClientAttrib()

The blit() method does this.

Use the pyglet.image.Texture.create() method to create

either a texture region from a larger power-2 sized texture,

or a texture with the exact dimensions using the

GL_texture_rectangle_ARB extension.

Texture internal format

pyglet automatically selects an internal format for the texture based on the source image’s format attribute. The following table describes how it is selected.

Format

Internal format

Any format with 3 components

GL_RGBAny format with 2 components

GL_LUMINANCE_ALPHA

"A"

GL_ALPHA

"L"

GL_LUMINANCE

"I"

GL_INTENSITYAny other format

GL_RGBA

Note that this table does not imply any mapping between format components and

their OpenGL counterparts. For example, an image with format "RG" will use

GL_LUMINANCE_ALPHA as its internal format; the luminance channel will be

averaged from the red and green components, and the alpha channel will be

empty (maximal).

Use the pyglet.image.Texture.create() class method to create a texture

with a specific internal format.

Texture filtering

By default, all textures are created with smooth (GL_LINEAR) filtering.

In some cases you may wish to have different filtered applied. Retro style

pixel art games, for example, would require sharper textures. To achieve this,

pas GL_NEAREST to the min_filter and mag_filter parameters when

creating a texture. It is also possible to set the default filtering by

setting the default_min_filter and default_mag_filter class attributes

on the Texture class. This will cause all textures created internally by

pyglet to use these values:

pyglet.image.Texture.default_min_filter = GL_LINEAR

pyglet.image.Texture.default_mag_filter = GL_LINEAR

Saving an image

Any image can be saved using the save method:

kitten.save('kitten.png')

or, specifying a file-like object:

kitten_stream = open('kitten.png', 'wb')

kitten.save('kitten.png', file=kitten_stream)

The following example shows how to grab a screenshot of your application window:

pyglet.image.get_buffer_manager().get_color_buffer().save('screenshot.png')

Note that images can only be saved in the PNG format unless the Pillow library is installed.